How to Navigate the Army Innovation Roadmap for Conducting Business in the Defense Marketplace - Part I

The Department of Defense ecosystem is gigantic and often overwhelming. Here are three examples of those who successfully navigated it

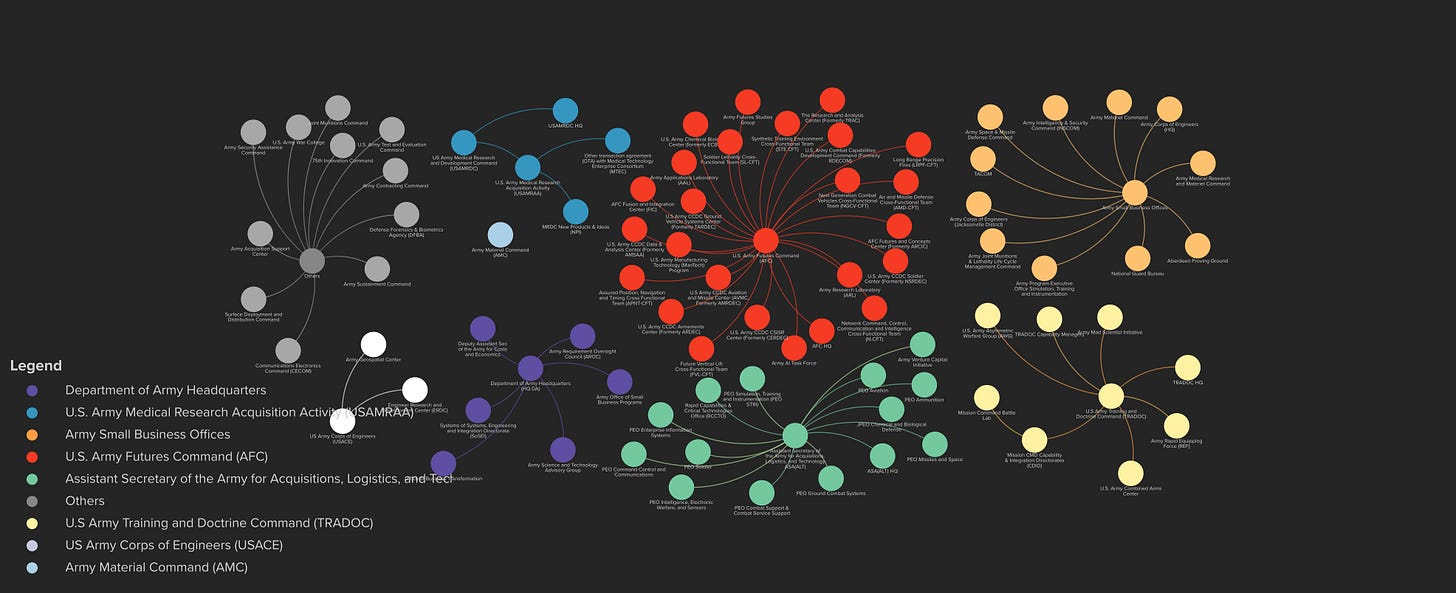

Follow the dots… The map below, although large, is a representation of the Army innovation landscape. With 88 unique organizational nodes, there are countless pathways companies can take between these departments to deliver their solution to an Army end-user. The questions many small businesses ask are, “How do I deploy my solution?” and “Which transition pathway should I use?”

The Department of Defense ecosystem is gigantic, often overwhelming and multi-level. We are serving up the landscape in (hopefully) bite-size portions and delivering maps up to you to by branch. This image is of the Army innovation landscape.

This map was created to help companies visualize and identify which Army organizations can help them deploy their product. Companies can determine which organizations might be useful based on assessing their own product maturity level and then identifying Army organizations that typically deal with that Technology Readiness Level (TRL). For instance, the Army Research Lab works with less mature solutions, while Program Executive Offices work with fully mature solutions.

So how do you know where to start? Let’s look at three pathway examples successful companies have taken:

1. Research Lab Pathway

As U.S. military vehicles fell victim to roadside bombs in Afghanistan and Iraq in the early 2000s, a small electric automobile company named Solectria (later purchased by Ceradyne and then 3M) was hard at work. Having developed a thermoplastic material superior to existing military-grade armor, Solectria sought opportunities to better protect vulnerable Army wheeled vehicles. Despite possessing cutting-edge technology and identifying an acute Army need, Solectria failed to attract support beyond early-stage pilot funding; that is until the company connected with the Army Research Lab (ARL).

ARL proved central to transitioning Solectria’s solution into an Army capability. ARL engineers recognized the value of the technology and identified an application around ballistic protection in helmets, instead of up-armoring Humvees. Moreover, ARL identified a partnership vehicle and funding to accelerate technological development through the Army's ManTech program. Through the ARL-ManTech pathway, Solectria was able to win contracts worth more than $100M with Army and Marine Corps fielding over 120,000 Enhanced Combat Helmets (ECH). Without the connectivity between ARL and ManTech, the Army and Marine Corps would have missed out on lifesaving commercial technology. Solectria’s involvement with the program helped them get acquired by Ceradyne, which was then acquired by 3M.

2. Operational Forces Pathway

The Operational Forces pathway is the most obvious. It is also the most difficult to navigate. For companies coming from the commercial market, the pathway may seem simple: find someone in the Defense Department who wants and needs your solution, get a contract with those users, and then sell. As simple as this is in the commercial market, it is a challenging feat in the defense market.

In the Defense Department and Intelligence Community, a single customer that (1) decides what to buy, (2) makes the purchase, and (3) uses the purchased product or service, as a single person performing each of these tasks, does not exist. By contrast, each of these three tasks are performed by one or more government personnel who are rarely located in the same organization or geographic area. Consequently, companies struggle to navigate this pathway because they are looking for three specific “customers” in a 2.2-million person haystack.

Instead, companies wanting to follow the Operational Forces Pathway should narrow down the department that would most benefit from their product and dive in at that point. Connecting with potential mentors or business leaders who have successfully navigated this path can also be helpful. Stepping off the path can be a minefield that can cause companies to waste valuable time. Companies moving through the Operational Pathway randomly pursue buyers and decision-makers. Through sheer brute force, companies can find the right combination of user, buyer and decision-maker, but often waste time looking for that combination and/or waste money developing different product prototypes for various customers all of which have a low probability of scaling.

3. Pathway of Least Resistance

An example of success with taking a path of least resistance is a data analytics company, called Valid Eval. Valid Eval was struggling to gain US Government traction until it was brought on as a contractor to perform data analytics for the Air Force’s Hyperspace Challenge Accelerator admissions process. The dollar amount was negligible, but the payout was significant as one of the judges (from the Army) fell in love with the platform.

Valid Eval engaged the Air Force to learn more about how the company could add value. The company quickly learned that Air Force users wanted their data analytics solution but lacked the contracting mechanism to actually purchase the software. Air Force users suggested Valid Eval pursue an Air Force Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) Phase I grant through AFWERX.

With the help of end-users that wanted their software, Valid Eval pursued and won $50k for a Phase 1 SBIR. The company then secured three memorandums of understanding from Air Force personnel wanting to purchase their solution, which helped Valid Eval win $750k in the second phase. Phase 2 funding provided a valuable pool of non-dilutive capital allowing the company to continue to get its products and services into program managers hands and build evidence of past performance without additional contracting friction.

However, the Air Force track ran cold as Valid Eval ran into a problem with getting accredited to run it’s software on government computers, called the Authority to Operate (ATO). Valid Eval was able to take the path of least resistance by pursuing Army work it had already started with the Hyperspace Challenge judge. Rather than fighting the Air Force ATO process, Valid Eval focused on Army prize competitions which didn’t have the same security requirements. Valid Eval has been with the customer for three years which indicates the benefit of the high switching costs faced by the government.

Valid Eval’s ability to stay flexible and nimble in their pathway to success ultimately led to a five-year IDIQ contract with a $10M ceiling with the General Services Administration. The contract provided the company with enough runway to transition interested Army and Air Force users into fully paid customers.

These three general pathways outline three strategies companies can take to find success. All pathways require companies to plan, strategize and map their route - just like reading a map or planning out a battlefield. You must literally connect the dots and forage your way until the end and your goal: a DoD contract.

Key Points:

Pathways will depend on your solution’s maturity and application.

Three general pathways can be useful to help you begin framing how you’ll enter the defense marketplace.

A novice looking at this landscape may get discouraged. It helps to have guidance from an entrepreneur or service member who has navigated a path before.

Stay tuned for more landscape roadmaps for the Navy and Air Force…

by Jeff Decker, program director and co-instructor of Hacking for Defense at Stanford University.