Why Minimum Viable Products are so Important

A Simple Napkin Sketch can Confirm or Deny a Hypothesis

The following is an excerpt from Chapter 1 in the NEW textbook Hacking for Defense, a graduate-level course taught at more than 70 colleges and universities worldwide and on three continents. More than 2,000 students have successfully completed its program.

The Hacking for Defense is predicated on the belief that a solution cannot be designed perfectly without feedback from those who experience the problem. Students gain feedback about the problems and potential solutions by testing hypotheses in interviews and using Minimum Viable Products. So rather than rolling the dice by building a solution without understanding the needs of defense personnel, MVPs are used to uncover important insights from interviewees about the problem(s) they face and the value they need before developing a solution. With all H4D tools, the goal in using MVPs is to accelerate learning while saving time.

A Minimum Viable Product, for the purposes of H4D, is the simplest thing that can elicit a response from a stakeholder and/or observe their behavior in interacting with it. Responses to the MVP are used to validate/invalidate a specific hypothesis determined in the Mission Model Canvas (MMC). At its core, the MVP is really just a prompt, sometimes as simple as a napkin sketch, to confirm or deny a hypothesis. It’s a conversation starter.

Many confuse a MVP with an early version of a product. Don’t get wrapped up in the word “product” in the term MVP. An MVP is not a finished solution, or even a prototype –– prototypes test how to build something, while MVPs test whether/how a user will benefit. The goal of using MVPs is to test and reject bad ideas early, so the team can learn what the stakeholders really need and avoid lengthy and unnecessary work building a solution no one wants.

The idea of the MVP is based on Steve Jobs’ comment that, “People don’t know what they want until you show it to them.” MVPs give potential users or customers something concrete to provide feedback on versus asking them to imagine a potential solution and then describe it. Just imagine asking someone to describe their perfect car. The description might be relevant to the team’s idea or it may not be. Now, imagine showing someone images of a car and asking them to provide feedback. The feedback provided on the images, or MVPs in this case, will be more descriptive and will focus on aspects of the car in which the team can then gain insights on (why else would certain images be selected!). Giving stakeholders or potential customers something they can point at and tell the team why they like or don’t like it is a far more powerful tool than relying on their imagination.

The purpose of MVPs is to learn, not “sell” the ideas. MVPs are used to gain feedback on those ideas. MVPs test MMC hypotheses that are core to understanding of the problem and potential solutions. Testing those hypotheses then capturing those insights needed to make small adjustments add to the understanding of the problem and/or solution faster. Making those small adjustments, or iterating, is the core of Agile Development. As such, MVPs will evolve over the class as they are validated or invalidated for the hypotheses. For example, one MVP might test a hypothesis about a problem afflicting a specific group of stakeholders. After validating that hypothesis, the next set of MVPs might aim to validate a series of hypotheses about what that group actually needs to solve the problem(s) previously validated.

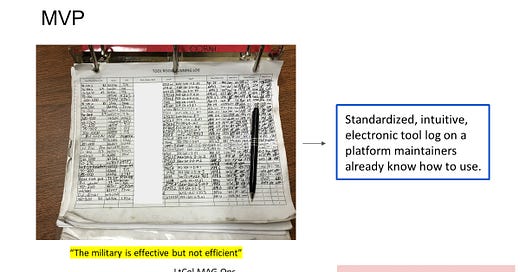

Above is an example of an MVP. It’s not much to look at and it took less than 10 minutes to create; it’s just an image of a log sheet that military stakeholders were using to conduct aircraft maintenance. Yet, the value of the MVP was significant. Team PredictiMx used the image during their interviews to learn about the current system’s shortcomings and insights into the value users needed to improve the maintenance process. The MVP was big juice for little squeeze.

The picture-based MVP elicited interview feedback that gave PredictiMx insights into what users wanted from a solution. The team developed a series of simple MVPs to validate whether the information they gathered was the opinion of a single person or represented the needs of the beneficiary group.

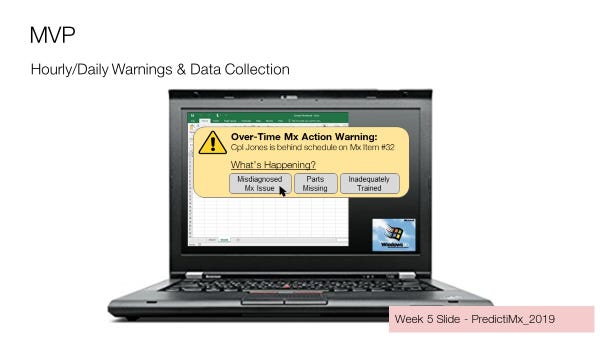

The above MVP was used by PredictiMx to validate whether defense personnel needed a warning when maintenance was not being performed as scheduled. Notice that the first MVP elicited responses from interviewees that they’d like a “warning alert.” This MVP sought to test the hypothesis that those personnel actually wanted this value, and if so, what the alert might look like.

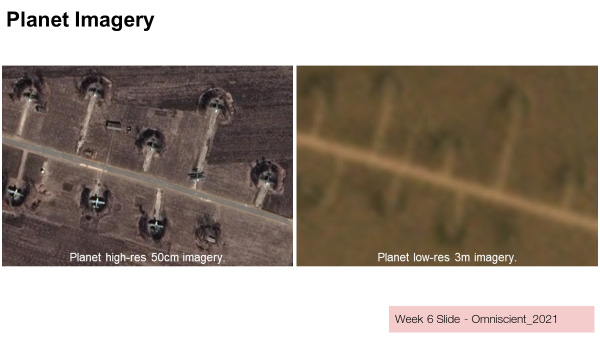

Team Omniscient used another 10-minute MVP to determine the exact needs of intelligence analysts. After six weeks of interviews, Omniscient validated that intelligence analysts would benefit from using computer vision to analyze satellite imagery. However, the team received conflicting feedback on the level of resolution analysts needed. Rather than continuing to ask intelligence analysts “What image resolution do you require to perform your job,” Omniscient designed an MVP slide (below) of the same picture depicted in two levels of resolution.

The outcome of using the MVP was that the team learned that the lower resolution image was sufficient for intelligence analysts. Note that the MVP took minimal time but led to maximum learning. The MVP effectively saved the team months developing a capability to read high-resolution images when the analysts only needed it to read low-resolution. This insight saved the team from wasting time and money developing a chainsaw to cut butter.

Using MVPs in Hacking for Defense

Using MVPs are used during Beneficiary Discovery interviews with stakeholders and follow a simple, but important, process. First, select one-to-two hypotheses from the Mission Model Canvas (MMC) that are to be tested. Second, develop an MVP that takes minimal time to build and can be shown to interviewees to test those hypotheses (sketches, photos, screenshots, wireframes are preferred!). Third, show the MVP to the beneficiaries prompting them to tell a story about how the MVP could add value and fit into their workflow. Be sure to tell the interviewees when introducing the MVP that it is based on feedback received from previous interviewees and took only 10 minutes to create. Doing so provides context into where the idea came from and invites the interviewee to provide critical feedback they wouldn’t otherwise provide if they thought the team had worked really hard to create the MVP. Fourthly, use the insights gained from the MVP to update the understanding of the problem and solution in the Mission Model Canvas. At this point, the process begins again as the team selects another set of hypotheses to test.

In summary, the MMC is used to track hypotheses. Hypotheses are then tested in Beneficiary Discovery by using MVPs. Feedback from interviewees is used to recalibrate MMC’s hypotheses which leads to a team’s iterative understanding of the problem and potential solutions. Remember, the purpose of using MVPs is to accelerate learning. The purpose of MVPs is not to sell early versions of a solution.

Want to learn more or be the first to read the textbook when it is published? Subscribe to the H4D Stanford blog at stanfordh4d.substack.com